YAYOI KUSAMA: AN INFINITE CONSCIOUSNESS DIRECTED AT THE COSMOS

My life, a dot: that is, one of a million particles. A white net of nothingness composed of an astronomical aggregation of connected dots will obliterate me and others, and the whole of the universe.1 Yayoi Kusama

In recent years, the practice of Yayoi Kusama, now in her eighties, has developed in astounding ways. Already, she has transcended gender and generation, coming to resemble no less than some eternal being liberated from the cycle of reincarnation. But, come to think of it, Kusama has defied categorisation for a long time, perhaps even transcending our very notion of art.

In the Asian view of the cosmos — in particular, the ancient Indian cosmology of the Vedic period — the fundamental principle of the universe involves that of Brahman, enveloping the entire cosmos, and Atman, the self, with the two connected by an invisible energy; while the unification of Brahman and Atman allows an escape from reincarnation and the endless cycle of life and death. This is an idea widely accepted by Brahmanism, Hinduism and the Jains. In Buddhism, however, though the idea of reincarnation and escape from its cycle by attaining nirvana is accepted, the Buddha stressed the cosmic connectedness of all things as causal interdependence, or pratītyasamutpāda. This way of thinking, which views human existence, consciously or unconsciously, as one part of the whole of creation believes in an invisible connectedness or relationship of cause and effect, and could also be described as the spatial concept underlying everything Eastern.

Contemplating Yayoi Kusama’s practice in light of this cosmic view, we begin to see how her awareness of existence shares this same vast sense of scale. The hallucinations, both visual and auditory, Kusama experienced from her younger years have been attributed to a nervous disorder known as depersonalisation syndrome. Those afflicted are said to perceive and experience the self as if observing from outside, divorced from their own mental processes and corporeal body. This is also explained by Kusama’s comment that, through the acts of painting and performance, ‘I have released this into a chaotic vacuum’;2 'this' being the mysterious something that only she can see and hear.

Installation view of Dots Obsession in 'Kusamatrix', Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2004 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Observing the nets and polka dots covering her canvases, and even those that extend over whole rooms — just as dots appear if we consciously study the voids in netting — we see that, for Kusama, these are the negative and positive of the same motif. Her all-encompassing mode of expression, in which these motifs stretch into infinity, may also be compared with action painting which was taking New York by storm in the 1950s, and with the mechanical repetition seen in Minimalism. According to Kusama:

When I’m painting netting on canvas, it runs from desk to floor and eventually all over my own body. By repeating the same thing over and over, the nets stretch into infinity. In other words, at that point I forget myself, surrounded by netting, and my hands and feet, the clothes I'm wearing, the whole room becomes filled with netting.3

One can interpret this as an act that eliminates the contours of things visible in the real world to reveal that everything in creation is interconnected. Consider, for instance, her series of sculptures covered in phallus-like protrusions, or her performances. One can readily arrive at a feminist interpretation of Kusama’s intention in producing these works, but, for the artist — who has a sexual fear of the phallus that comes from childhood experience 4 — to use the object of fear repeatedly as a motif in her work was an act aimed not so much at the liberation of women, generally, as it was intended to inform the liberation of Kusama herself, in an example of ‘psychosomatic art’.

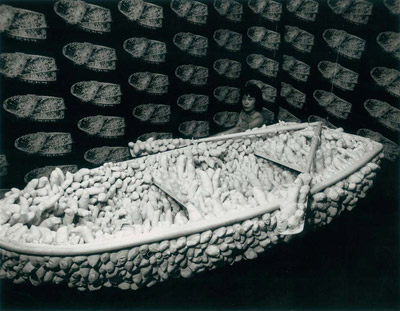

Kusama at her 'Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show' exhibition, Gertrude Stein Gallery, New York, 1963 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

In fact, Kusama’s mode of expression expanded from the likes of painting and performance in an environmental direction, employing entire spaces and extinguishing the contours of objects contained therein with nets and polka dots. In her 1963 solo exhibition at the Gertrude Stein Gallery titled ‘Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show’, 999 black-and-white photographs of a 10-metre boat covered in sprouting, stuffed, phallus-like objects were stuck all over the floor, walls and ceiling of the gallery, while in 1964’s ‘Driving Image Show’ exhibition, the floor was covered in macaroni. In Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field 1965, she presented a room made from mirrors and plastic, and in the 1966 exhibition titled ‘Kusama’s Peep Show: Endless Love Show’ she showed Endless Love Room, consisting of blinking red, white, green and blue lights in a hexagonal-shaped, mirrored room. Such works marked the dawn of installation art, which began to attract enormous attention internationally in the 1990s. At the same time, perhaps it is only natural that within this artistic current, which first flowed in the 1990s, Kusama’s installations — her spaces crammed with dots and firefly lights, and which often appeared to be infinite in scale courtesy of mirror effects — are now much more widely appreciated.

Installation view of Fireflies on the water 2000, Le Consortium, Dijon, France, 2000 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Kusama is engaged in a never-ending mission to release the microcosms within herself to the outside, in order to project it on the macrocosms and the infinite space to which our imaginations do not extend. By facing up to this endless mission, Kusama herself is also elevated to the status of eternal being, so to speak — one who, though but a speck of dust in the universe, also has a bird’s-eye view of the entire universe. It is her infinite consciousness that transcends the time, generation, gender, region and culture, as well as the various vocabularies of contemporary art. It is also the reason Yayoi Kusama is so well-received around the world — and the reason why the force driving her is like an eternally bubbling spring.

Mami Kataoka is Chief Curator, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.