SPECIFIC OBSESSIONS: READING KUSAMA THROUGH MINIMALISM

On the occasion of Yayoi Kusama’s first United States retrospective in 1989, a pivotal moment in the artist’s reappraisal outside Japan, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith observed that ‘The 1960s are not so long ago, yet the art history of the period already has its gaps’.1 Smith was writing of an art history that had been shaped in and by New York, which, by the time Kusama arrived there in 1958, was already staking its claim as ‘capital of the art world’. Kusama was not the only artist up for reconsideration — the biennale boom would soon see the geographical limits of art explored in earnest. The complications that Kusama’s rediscovery produced for American art history are well documented — she is now generally regarded as a significant precursor to 1960s Pop and minimal art, in addition to being a significant contributor to contemporary art. Kusama is a unique figure, and her output has consistently eluded grouping within artistic trends. Nevertheless, it remains critically productive to consider Kusama’s work in dialogue — and often in anticipation — with that of her contemporaries, if only to increase the range of perspectives from which her artistic development and current practice may be considered.

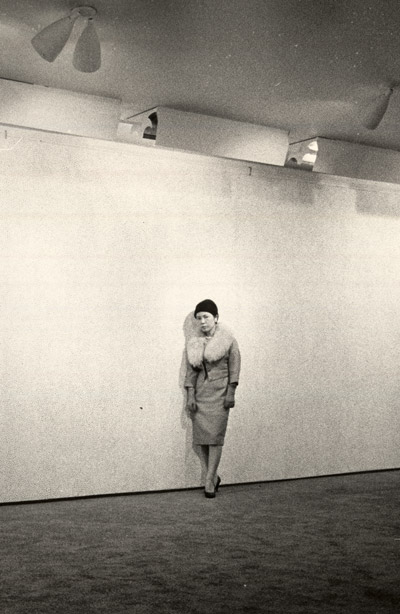

Kusama with a ten-metre net painting, Stephen Radich Gallery, New York, 1961 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Minimal art, or Minimalism, was one of the major artistic tendencies to emerge from the United States in the 1960s. Though never a unified movement — the majority of the artists associated with it actively rejected the term — it described a significant trend toward interrogating the communicative authority of the artist and the exalted status of the art object by reducing it to its basic components. The term is notoriously slippery, but it has generally come to be associated with the reductive paintings, sculptures and ‘specific objects’ — neither paintings nor sculptures — of Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Blinky Palermo, Richard Serra and Frank Stella, occasionally extending to Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt, Anne Truitt and others. Unlike many of their abstract expressionist predecessors, the minimalists steadfastly avoided emotionally charged gestures, often to the point of having their works industrially produced. Minimalism did not emerge in isolation, developing in dialogue with Pop art, colour field painting and concrete art. Nor was its prominence particularly long-lasting; indeed, part of the tendency’s importance was the influence that its questioning of artistic convention had on subsequent developments like conceptual art and Postmodernism.

When Kusama arrived in New York in 1958, the city’s powerful art scene was still in thrall to the legacy of Abstract Expressionism. The net paintings she began producing shortly after her arrival, and first exhibited the following year, were therefore received as a major revelation. Abstract expressionist critic Dore Ashton called her show a ‘striking tour de force’,2 while Sidney Tillim declared the artist ‘one of the most promising new talents to appear on the New York scene in years’.3 Though never a ‘pure’ monochrome painter, Kusama was one of the few artists working in the city who proposed that a surface could be reduced to a single, undifferentiated field, unbroken by figuration or abstract compositional devices. As Donald Judd observed on first encountering the works, her net paintings took the expansive colour fields of ‘cooler’ abstractionists like Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and Barnett Newman as a point of departure, but added something entirely new. In his review of the exhibition for Art News, Judd described the paintings as ‘strong, advanced in concept and realised’. He continued:

The space is shallow, close to the surface and achieved by innumerable small arcs superimposed on a black ground overlain with a wash of white. The effect is both complex and simple. Essentially it is produced by the intersection of two close, somewhat parallel, vertical planes, at points merging at the surface plane and at others diverging slightly but powerfully.4

Unlike Abstract Expressionism, the optical effects of the net paintings’ undulating fields owed more to the material qualities of the painted surface than to any illusions of pictorial depth. Nor was their composition bound by a relationship to the painting’s frame; they were, as Kusama herself described them, ‘without beginning, end or centre’.5 The nets propagated according to their own internal logic, a system in which they could go on reproducing themselves across an entire room if it weren’t for the edge of the canvas, which, as a limit, was purely physical, rather than structural. This suggested that painting might be considered as a phenomenal, rather than illusory, practice — a painted surface could be thought of as a single plane of a three-dimensional object, rather than a two-dimensional pictorial ‘window’.

Infinity nets 2000 / Synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 162 x 130cm, The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2001 with funds from The Myer Foundation, a project of the Sidney Myer Centenary Celebration 1899–1999, through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery

This is a reductive reading of the works, of course, as their origins lie in slightly earlier paintings in which Kusama had attempted to reproduce the bird’s-eye view of the Pacific Ocean she experienced on her flight from Japan to the United States. This, in turn, corresponded to the character of her childhood hallucinations, in which objects surrounding her were unified under a single pattern. Further, there is a performative dimension to the net paintings — their vast accumulations of tightly painted whorls suggesting monumental dedication to painstaking artistic labour, which Kusama has characterised as both obsessive and therapeutic. Yet, Judd’s account of the paintings is wholly in keeping with the critical language of the time, operating firmly within the formalist framework established by Abstract Expressionism. Moreover, it was an assessment to which Kusama assented, at least initially. Judd, yet to make a name for himself as an artist, became close to Kusama — for a time, the two were involved romantically6 — and assisted her in the production of the ‘Accumulation’ sculptures that reinforced the net paintings’ implication of the redundancy of the canvas, a decisive shift away from two-dimensionality that Judd would cite approvingly in his influential 1965 essay ‘Specific objects’.7