SPECIFIC OBSESSIONS: READING KUSAMA . . . CONT

Compulsion Furniture (Accumulation) c.1964 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Begun in 1961, the ‘Accumulations’ series of works mark an interesting point of comparison between Kusama’s oeuvre and minimal art. These sculptures consisted of pieces of found furniture covered in small, sewn protuberances. Formally, they suggested that the nets previously limited to the pictorial plane had finally exceeded the canvas and assumed three-dimensional form, covering every available surface. Metaphorically, they are most often interpreted as phalluses, a device with which the artist confronted her own deep-seated sexual anxieties. But their position within Kusama’s practice at the level of presentation is worthy of consideration — the ‘Accumulation’ would themselves accumulate, to the point that, by the time of Kusama’s 1964 exhibition 'Driving Image Show', they constituted a complete environment. That exhibition presented virtually all of the artist’s ‘Accumulations’ to date, crowded together to create a single installation, a work indistinguishable from the medium of the exhibition itself. In turn, it can be seen as an important precursor to the ‘Infinity Mirror Rooms’ that Kusama would first present the following year — her 1966 Venice Biennale work Narcissus Garden — and the prevalence of immersive installations in Kusama’s practice following her ‘rediscovery’ by the international art world in 1989.

Certainly, the position espoused by Judd in 1965 was one that found the metaphorical and illusory attributes of art objects to be less powerful than their physical presence. A psychoanalytic account of Kusama’s ‘Accumulations’ is notably lacking from Judd’s ‘Specific objects’; while their intense and obsessive character is noted, interpretation is limited to describing them as ‘strange objects’. Nevertheless, the essay proved fertile ground for discussion of the general shift away from painting occurring in New York’s art world at the time. A significant theoretical contribution to minimal art was made by Robert Morris, whose 1966 essay series ‘Notes on sculpture’ developed Judd’s observations along phenomenological lines.8 Morris placed his emphasis on the production of forms producing ‘gestalt sensations’ — the experience of an object’s constituent parts as a sensory unity, without ‘perceptual separation’ between such properties as colour, texture, scale and mass. These sensations had the catalytic function of making viewers aware of their own presence in relation to the object under contemplation, and to the conditions of its appearance.

Soul under the moon 2002 / Mirrors, ultra violet lights, water, plastic, nylon thread, timber, synthetic polymer paint | 340 x 712.1 x 600cm (installed) / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2002 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer and The Myer Foundation, a project of the Sidney Myer Centenary Celebration 1899–1999, through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation and The Yayoi Kusama Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Appeal / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery

In this sense, the contemporary understanding of installation art as edifying spectacle, an assessment that has not excluded Kusama’s installations, is somewhat problematic.9 It is arguable that the spectator consistently has the opportunity to become aware of their own presence in her works, no matter how seductive, and that succumbing to the temptation to be uncritically mesmerised is an entirely subjective and voluntary decision. Where a subject’s presence is not directly visualised within the work, it can be experienced kinaesthetically, as a result of bodily movements undertaken in order to apprehend larger-scaled works. This is not to say that a critical perspective necessarily arises from an encounter with Kusama’s work. But, by the same token, such a perspective is never precluded by it.

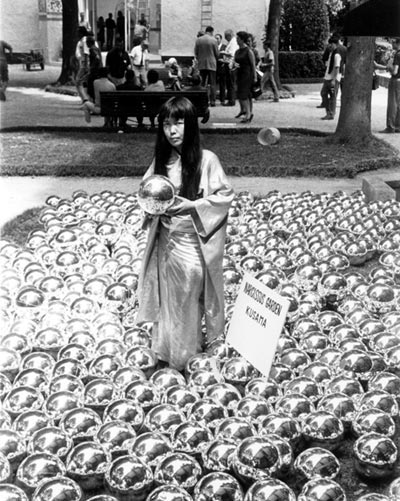

Yayoi Kusama with Narcissus Garden, Venice Biennale, 1966 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio inc.

Indeed, the presentation of Narcissus Garden at the 1966 Venice Biennale has been interpreted as an early realisation of the institutional critique implicit in phenomenological theories of minimal art, in the sense that it directed attention to the conditions of its display — an idea also being explored in the emerging field of conceptual art. The 1500 silver balls that Kusama displayed on the lawn of the Italian Pavilion effectively inverted the operation of the mirror rooms, directing their reflection outward to take in their immediate surroundings, distorted and repeated across the balls’ shiny surfaces. During the opening week of the exhibition, Kusama, who had been photographed cavorting with the balls in various poses, took to selling them to passers-by for the extremely low price of 1200 lire, or $2. This action, which has been interpreted as a comment on the commercialisation of art, raised the objection of Biennale officials, who ejected her from the exhibition for conflating art with ‘hot-dogs or ice-cream cones’.10 The institutionally critical function of this guerrilla action is self-evident, but it is also worth noting the degree to which the audience was made complicit in the artist’s action by their participation in the exchange. The correspondence between participation and critique would be further explored in the and ‘Body Festivals’ Kusama would stage over the next few years, with targets ranging from New York’s Museum of Modern Art to the New York Stock Exchange.