SPECIFIC OBSESSIONS: READING KUSAMA . . . CONT

Kusama’s interaction with Minimalism is complex. For example, with its sensuality and ebullience squarely positioned in the realm of popular culture, Kusama’s confrontational participatory performances, from 1967 until her return to Japan in 1973, bear scant resemblance to minimal art. Yet, they were informed by a development of the very concerns with which Minimalism found so many sympathies — an insistence on the primacy of the material characteristics of the art object, and a challenge to the notions of the work of art as self-contained entity, and of the artist as the exclusive repository of cultural meaning. At the same time, even Kusama’s work prior to 1967 contains substantial divergences from that of Judd, Morris and others. In contrast to Minimalism’s effacement of gesture, the expansive planes of the net paintings are achieved not through reduction, but through the extraordinary process of accumulation, their anxious arcs and organic fluctuations contrasting visibly with the deadpan geometry of contemporary works by Frank Stella, Ad Reinhardt and Tadaaki Kuwayama. While her eschewal of mystical and orientalist interpretation of abstraction agrees with Judd’s fiercely materialist stance, Kusama remains open to psychoanalytic interpretations of her work, which results in a manifest sensuality and irruptive humour typically absent from much minimal art. Serial production in Minimalism is often read alongside that of Pop art as a critical evocation of mass production and industrial society. For Kusama, repetition has a more immediate therapeutic function, while introducing the paradox of destabilising the modernist fetish with novelty even while the artist pursues aesthetic innovation — if nothing else, it confuses linear understandings of the progression of time.

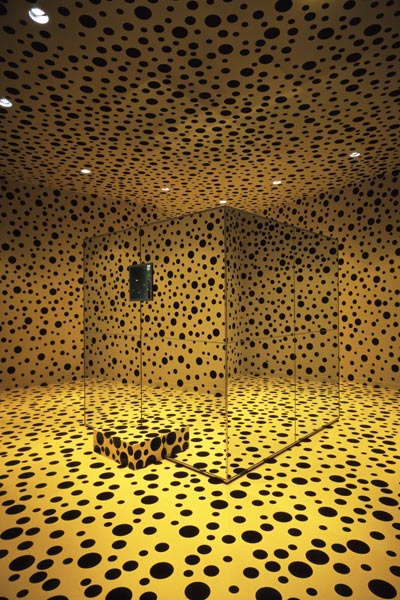

Mirror Room (Pumpkin), outside view, Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Japan, 1991 / Image courtesy: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / © Yayoi Kusama, Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Never registering perfectly with minimalist orthodoxy, Kusama’s work is perhaps better considered as having overlapped it in both time and space. Strong arguments have also been made for her relevance to the ‘post-minimalist’ art of her friends Eva Hesse and Carolee Schneemann, and her role in the development of American Pop and European concrete art have been significant factors in the widespread recognition Kusama now enjoys.11 To a large degree, this is merely backstory — Kusama continues to produce compelling and challenging work, and should not be beholden to a single historical moment. Nevertheless, her works’ dialogues with Minimalism and its particular positions on spectatorship remain relevant and informative — as does Minimalism itself. One example of a reciprocal reading might be found in Mirror Room (Pumpkin) 1991, one of the first major works Kusama produced after her international rediscovery, and part of her contribution to the Venice Biennale of 1993. A peepshow-style mirror room filled with small pumpkin sculptures, the installation was significant in that the room also featured mirrors on its external walls, reflecting the gallery walls in the manner of the classic minimalist cube. Even her recent Reach Up to the Universe, Dotted Pumpkin 2011 may be read as a mutant version of the cube — its just-larger-than-a-human scale sitting precisely between that of ornament and monument that Morris defined as the field of minimal sculpture. Minimalism’s identification of the phenomenal and critical potential of such work is important, particularly at a time when the presentation of art is so heavily geared toward the production of the kind of immersive, interactive and participatory encounters Kusama pioneered in the 1960s, and which she continues to refine in her engaging and provocative practice.

Reuben Keehan, Curator, Contemporary Asian Art,

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

ENDNOTES

- Roberta Smith, quoted in Love Forever: Yayoi Kusama 1958–1968 [exhibition catalogue], Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles 1998, p.187.

- Dore Ashton, quoted in Love Forever, p.12.

- Sidney Tillim, quoted in Love Forever, p.170.

- Donald Judd, ‘Reviews and previews: New names this month’, Art News, October 1959, reprinted in Judd, Complete Writings 1959–1975, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Canada, 1975, p.2.

- Yayoi Kusama, quoted in Alexandra Munroe, ‘Art of perceptual experience: Pure abstraction and ecstatic minimalism’, in The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989 [exhibition catalogue], Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2009, p.293.

- Kusama discusses her relationship with Judd in Infinity Nets: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, Tate Publishing, London, 2011, pp.179–81.

- Donald Judd, ‘Specific objects’, Art Yearbook 8, 1965, reprinted in Complete Writings 1959–1975, pp.181–89.

- Robert Morris, ‘Notes on sculpture’, reprinted in Gregory Battock (ed.), Minimal Art, EP Dutton, New York, 1968, pp.222–35.

- A thorough account of debates around installation can be found in Claire Bishop, Installation Art: A Critical History, Routledge, New York, 2005. Appropriately, the critique of installation art as spectacle has its origin not in the theory of spectacle as outlined by Guy Debord, but in Michael Fried’s pointed contemporary critique of the theatricality of Minimalism (or ‘literalism’) in ‘Art and objecthood’, reprinted in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1998, pp.148–72.

- Quoted in Love Forever, p.180.

- A significant case for these connections is made in contributions by Lynn Zelevansky and Laura Hoptman to Love Forever.